Happy Feet, Happy Beat, Happy Socks: How Mac Churchill uses humor to fight cancer

By Scott Nishimura

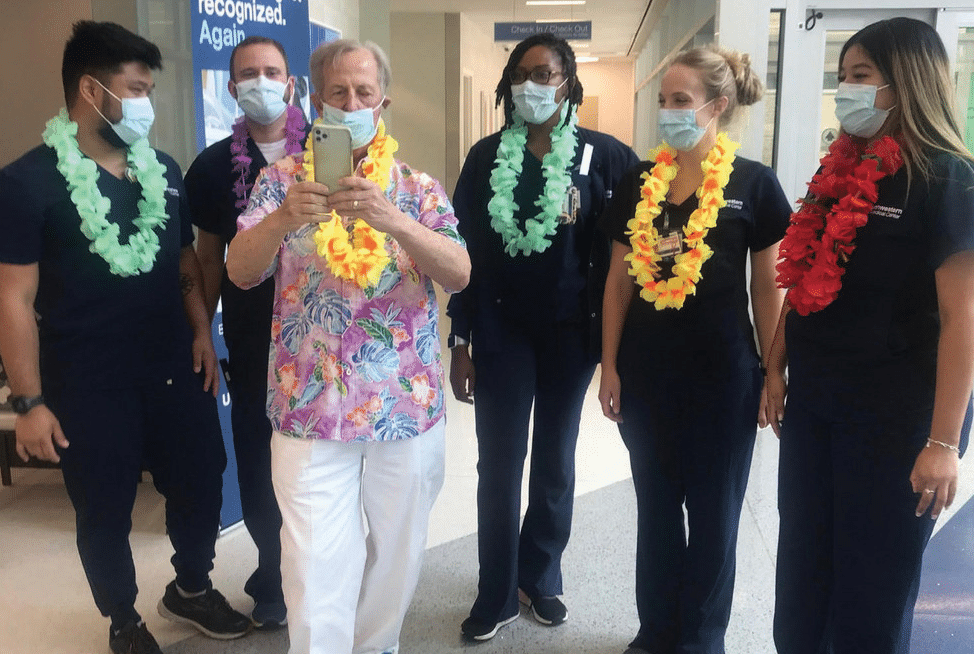

Photo courtesy of mac Churchill

It was appropriate. Having to reschedule a doctor’s appointment, Mac Churchill picked up the phone and called with an offbeat excuse. “The appointment you have for me interferes with my senior pole vaulting tryout,” he deadpanned.

Showing up for the next appointment, Churchill learned his supposed pole vaulting prowess had become a topic of interest among the nurses. “Fifty percent say they think you’re in pole vaulting,” one told him. “The other half don’t think you are. But they’ve all made bets. And there’s money riding on it.”

Churchill’s response: “I’ve taken up bull riding. It’s only eight seconds long.”

This is how Churchill came to terms with that “devil” – his cancer. Diagnosed in 2014 with blood cancer and subsequently with squamous cell cancer, he’s undergone chemotherapy and radiation regimens and several surgeries, including disfiguring ones that will require a reconstructive procedure. Amid that, Churchill turned to humor. He uses it to lift his healthcare team and patients he encounters, and he helps himself in the process.

Churchill, a retired longtime Fort Worth auto dealer, cast off the “blacks and grays” he says many other cancer patients wear to “blend in,” in favor of floral print shirts and colorful socks that he calls his “happy socks.”

His jokes are nonstop. “What channel is the porn on?” he asked one provider during a visit.

After one course of radiation treatment, Churchill threw a Hawaiian-themed party and presented leis to the technicians, calling them his “A Team.”

“Most of them were working on other patients,” he said during a recent interview at his home in west Fort Worth.

His approach has worn off on members of his healthcare team, Churchill, 74, says. At one appointment, a nurse came in, wearing colorful socks, shoes, a headband and earrings, he says. “I knew you were coming,” she told him.

Churchill is working on a book he’s tentatively titled “Happy Socks,” offering insights from his journey, a section on salesmanship and more stories and jokes, including one about a nurse’s catheter extraction after one of his surgeries.

“If you can make that funny, you can make anything funny,” he says.

Churchill says he approached his original diagnosis in denial. “You start off with denial, and you sure don’t want anybody else to know it.”

Then he switched tactics. “I kind of put on my badge of defiance, looking at that devil that was cancer, saying I’m going to beat you,” he says. “I’d tell the caregiver what that was all about.”

His healthcare team members anticipate his visits, he says. “They look forward to seeing me because I’m positive, I’m not negative,” he says. “When you’re going through cancer, you become very self-centered.”

Churchill says he works out three times a week and still plays golf, even though “I can’t raise my arm much higher than that,” he says, lifting his arm parallel to the floor.

His physician asked to record Churchill’s golf swing and show it to another patient despondent over illness. “It wasn’t pretty,” he says.

Churchill says he tries to interact with everybody he encounters. “One of the keys is finding out their name and their personal story and having a relationship with them,” he says. “You reduce stress and anxiety for everybody for maybe a moment.”

He hopes his story helps others traveling a similar road.

“It should be inspirational to a lot of people,” he says. “It should cause them to look at their caregivers differently. And by taking an interest in their caregiver, the caregiver begins to look forward to their next appointment with you and they seem to take better care of you.”