At Home With The Maestro

By Tori Couch

Photos by Ralph Lauer

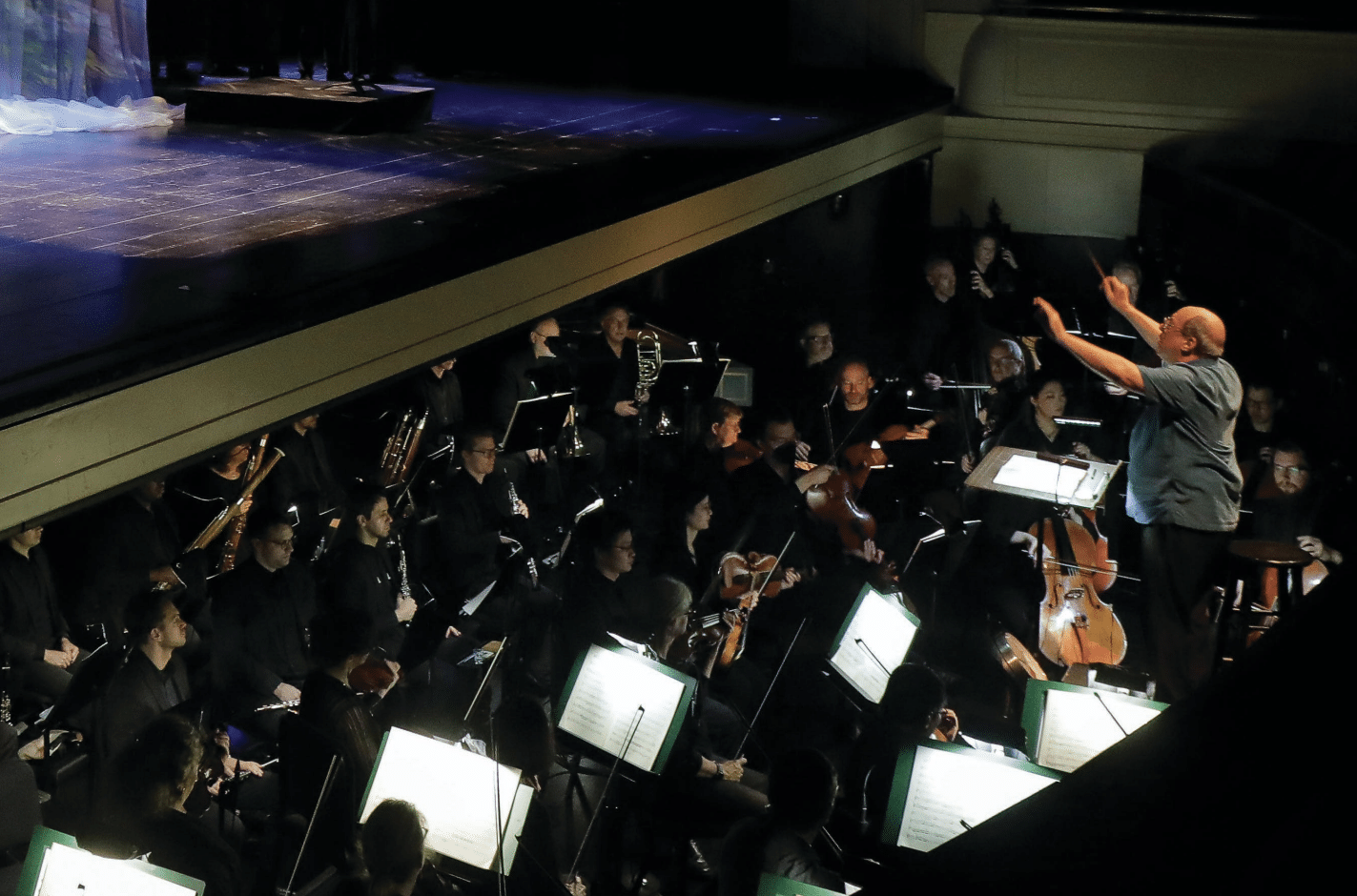

Exploring the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra’s first year — and things yet to come — under Music Director Robert Spano

Robert Spano’s personal library could make an English, religion or philosophy professor blush.

The books Spano “loves to look at” greet him as he walks in the door of his condo at the Texas & Pacific Lofts in downtown Fort Worth.

They include multivolume collections, such as the “Groves Dictionary of Music and Musicians” and the 13-volume, original edition of James George Frazer’s “The Golden Bough.”

The living room wall houses fiction, biographies, plays, scripts, literary criticisms, essays and poetry. In the office, works on psychology and Christian theology fill several shelves. Philosophers and thinkers highlight another wall, and the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra music director arranges them in a specific way.

“I put them in alphabetical order, and I know they’re going to hate being next to each other because they’re all gonna argue,” Spano said. “And I think they should.”

Finally, over in world religions, Spano’s selections cover ancient Greek beliefs, Taoism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Islam, Judaism and Jewish mysticism.

The books arrived in 140 boxes and are just a portion of Spano’s entire library, which had gone into storage for three years. What’s more impressive is the self described biblioholic’s sense of recall: He described the collection from memory while sitting in the lofts’ resident lounge on a morning in late May.

“I’m sorry I wouldn’t let you in the house,” he said. “I’m still moving basically. It’s been a year, but I’m still moving. I’ve still got boxes all over the place.”

Considering Maestro Spano served as a guest conductor around the country over the past nine months and then hopped on an airplane days after this conversation to direct the Aspen Music Festival and School summer programming, it’s understandable that boxes remain unpacked.

The annual trip to Aspen, where Spano has been music director since 2011, capped his inaugural season as the symphony’s music director in Fort Worth.

During that 2022-23 season, Spano and symphony CEO and President Keith Cerny reimagined performances based on a vision called Theater of a Concert. This brought new experiences to Bass Performance Hall, including a collaborative performance of Stravinsky’s “The Firebird” with Texas Ballet Theater and an interactive staging of the oratorio “Haydn: The Creation.”

More collaborative performances and the third year of the Chamber Series at the Kimbell Art Museum are scheduled for the 2023-24 season.

Spano first connected with the symphony in March 2019, as it sought a successor for music director Miguel Harth-Bedoya. Mercedes Bass, chair of the symphony board, asked Spano to serve as principal guest conductor, and he accepted. Bass and Spano had met through Aspen, where she is a trustee of The Aspen Institute and serves on the festival’s school advisory board.

Spano — who spent the previous 20 years leading the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra — has ushered in quite a few changes in Fort Worth. So many, in fact, that Cara Owens, assistant principal bassoonist, said the symphony has entered “a brave new world.”

ADAPTING AMID A GLOBAL PANDEMIC

Owens and Michael Shih, concertmaster/violinist, have both been in the orchestra for over 20 years, playing under Harth-Bedoya and numerous guest conductors.

“Robert has this wonderful, warm style that he invites all of us in,” Shih said. “When we rehearse, you really feel like you are part of this vision that he’s trying to create.”

Owens also used the word “inviting” when describing Spano’s rehearsals. The organization and vision for each rehearsal is its own art form, she said.

“There’s no rehearsing in such a manner you get to the end of the two-and-a-half hours and you feel like there’s still so much more to do,” she said. “He covered everything he clearly wanted to cover.”

Spano began his tenure as music director in August 2022 after starting as music director designate in April 2021. He initially signed a three year contract and recently agreed to an extension through the 2027-28 season.

Spano hit the ground running by hiring almost a dozen tenure track musicians. These vacant positions could not be filled while the symphony was between music directors.

Even though Spano had interacted with the orchestra before, as the new music director he wanted a better understanding of the group’s immediate needs, wants and goals. So he held eight lunch meetings with eight musicians at a time until he met everyone.

“Maybe one of the best things that came out of that process for me is how committed they are to this orchestra, to themselves and to each other,” Spano said. “How important it is to them and how invested they are in the enterprise. That’s not true everywhere. There’s a real spirit in the orchestra.”

Spano saw that spirit on full display while guest conducting at a symphony performance in January 2021 amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

It was his first live performance since COVID forced shutdowns across the country in March 2020 and paused live in-person performances.

Cerny and the symphony worked tirelessly to bring back safe, live performances. The organization even kept staff members and musicians on the payroll, said Cerny, who joined the symphony in 2019 and was deep into the music director search when the pandemic hit.

The 2020-21 season started in September 2020 at Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium, since Bass Performance Hall did not reopen in time.

“We were one of the first orchestras in the country to [perform live],” Cerny said. “We’re really proud of that.”

COVID performances looked very different from the pre-pandemic days. Instead of musicians forming a tight semicircle around the conductor, they were spread out in a straight line, with 6 feet between each musician and plexiglass separating each row. Musicians had monitors near them, so they could hear other instruments and try to play together. Conductors needed a microphone to address the entire orchestra.

The music might not have been perfect, but the performances provided everyone involved a taste of community and an escape from isolation.

More than two years later, Spano’s eyes light up behind his black rimmed glasses while recalling the January 2021 performance in Fort Worth.

“It was so inspiring to be at Will Rogers during that period,” Spano said. “It was a lifesaver.”

Mollie Lasater, a symphony board member since 1986, remembers the performance well. There was no intermission or planned break, but at one point, Spano paused and turned to the audience.

“He said, ‘I just have to take a moment to tell you that this is a wonderful orchestra and this is the first time I’ve been able to conduct live in a whole year,’” Lasater said. “It just brought the house down.”

Another boon to the symphony’s pandemic years was the $8.1 million in government assistance it received, including from the Paycheck Protection Program.

But with that aid ending, Cerny is looking ahead.

He has prioritized expanding the board, bringing in more audience members and finding more fundraising avenues. A tentative budget projection for 2023-24 is more than $15.5 million, Cerny said. The budget in 2022-23 was $15.1 million.

“Three years in COVID, we were able to have essentially balanced budgets, so that was great,” Cerny said. “This year, we’re raising money as fast as we can.”

Cerny negotiated a new three-year contract with the musicians last year. He is also committed to gradually increasing the orchestra’s physical size. The symphony hopes to add one new core orchestra member per year during the first three years of Spano’s tenure, Cerny said. Currently, the orchestra has 68 core members.

With Spano on board, the symphony’s artistic vision is changing, too.

Spano was already thinking about taking the music director position around the time of the January performance, although it didn’t fit his initial post-Atlanta plans. He had wanted more freedom in his schedule and an opportunity to do things differently. But a new path formed when Bass presented Spano with the idea of being the symphony’s next music director over dinner in late 2020. The symphony announced Spano would become its 10th music director in February 2021.

“I got excited about the idea and realized I could change my plans for what was coming next in my life,” Spano said. “It’s been a wonderful thing already.”

THEATER OF A CONCERT

As Tim O’Keefe watched Texas Ballet Theater perform the 1919 version of Stravinsky’s Suite from “The Firebird” on the Bass Performance Hall stage in April with the symphony, the ballet’s acting artistic director could only imagine what the dancers were experiencing.

“I was so happy for the dancers, because they had that wall of music behind them,” O’Keefe, a former dancer, said. “It must have been so fantastic.”

O’Keefe choreographed the 22-minute dance for the symphony’s “A Night at the Ballet” show, which included visiting composer Brian Raphael Nabors and music from Humperdinck, Griffes and Ravel.

The large-scale collaboration stemmed from Cerny and Spano’s Theater of a Concert vision.

“A concert is inherently theater,” Spano said. “Then the notion is how do we enhance the theatricality of the experience. What things contribute to the enjoyment of the audience and of the performers as well. How do we make the most of that reality?”

The Theater of a Concert concept covers a wide range of additional elements and even minor enhancements, Spano said, like interviewing a composer onstage.

The “Firebird” performance was part of a three-year Stravinsky ballet series that continues into 2023-24 with Dallas Black Dance Theatre performing “Petrushka.” Cerny is in talks with a third ballet company for the 2024-25 season and had nearly 80 percent of that season planned in May.

Spano and Cerny both have experience with collaborations and find that they stretch the audience’s frame of reference around a particular piece of music, Cerny said.

“I’ve said [“Firebird” is] truly one of the most exciting projects I’ve produced in my career,” he said. “People say, ‘Why?’ It brought all these elements together that you don’t normally see.”

Each collaborative project requires detailed, long-term planning.

About 18 months before “A Night at the Ballet” became a reality, Cerny and Spano approached O’Keefe. He jumped at the opportunity and spent countless hours on Zoom calls with symphony staff, working out performance logistics.

Figuring out how 12 dancers and the full orchestra would share the stage took strategic thinking. Limited stage space forced unique prop placement, such as hanging from the ceiling the egg where the antagonist Koschei puts his soul.

O’Keefe started rehearsals about three-and-a-half weeks before the performance. Because Spano’s schedule prevented him from attending rehearsals until production week, O’Keefe sent videos so Spano could offer feedback. Cerny attended some rehearsals and provided additional guidance.

During that time, O’Keefe noticed the version of “Firebird” that Spano picked went a little fast for the dancers. Spano happily accommodated O’Keefe’s tempo adjustment request.

“He was such a pleasure to work with, but you could tell he was just as interested in our needs,” O’Keefe said. “Where we were coming from and how we were expressing the music as opposed to how he would express the music and combining that together.”

A month after the “A Night at the Ballet” performance, the symphony continued the Theater of a Concert concept. Seraphic Fire, a Miami-based vocal ensemble, and three vocal soloists helped present “Haydn: The Creation.”

The orchestra stayed in the pit while singers moved around onstage and images relating to the lyrics were projected on screens and a draped sheet. A digital box above the stage translated the German oratorio into English.

Next season, a collaboration with the Calgary-based touring group Old Trout Puppet Workshop will bring Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf” to life with large puppets while the orchestra plays. The symphony will continue doing traditional symphonic performances but occasionally add elements. Collaborating remains a priority.

“Part of our mission is to be mindful that we have these multiple audiences that we want to take care of and appeal to and attract and invite,” Spano said. “The variety is necessary if we’re to do that.”

The musicians enjoy engaging with other performing arts groups, too.

“The various forms of art don’t exist in vacuums,” Owens said. “Collaboration is what it’s about. It just adds depth.”

Each season also includes the Chamber Series at the Kimbell Art Museum, a program Spano and Cerny started during the 2021-22 season. It can highlight composers who might not drive ticket sales at Bass Performance Hall or spotlight music intended for smaller ensembles and a more intimate setting, Cerny said.

Spano has played the piano and performed some of his compositions through the Chamber Series. Principal musicians from the symphony have also participated and shared music with audiences of up to 250 people. In October, Cerny is performing Bartók’s “Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion” with the symphony’s pianist.

The Theater of a Concert vision will keep evolving over the next five seasons. Spano’s music industry connections and depth of experience conducting orchestras, choirs, symphonies, operas and ballets constantly brings new ideas, Cerny said.

A joyful personality and a passion for music make the planning process more enjoyable, too.

“It’s one of the absolute high points of my job, because he’s such a great colleague,” Cerny said. “Ultimately, he has final say on many things, but we go through this very intentional, really carefully thought-through process that is so rewarding and tied to the Theater of a Concert strategy.”

Spano echoed those feelings when asked about working with Cerny.

“Keith and I were laughing the other night that we never should have been allowed to work together, because we egg each other on,” Spano said. “We share a very similar passion around live performance, fascinations with what’s possible and what we’d like to explore.”

TURNING PASSIONS INTO A CAREER

Spano focuses on the symphony most of the year, but as June approaches, the Aspen Music Festival and School garners all the attention.

Spano has been involved with the festival in some capacity since 1993. He now directs the Aspen Conducting Academy, and oversees programming for more than 300 events and educational programs for 630 students and young performers.

Aspen is where board member Lasater first saw Spano in action. She and her husband have attended the festival for years and financially supported it for more than two decades.

Lasater and her husband, as well as her grandchildren, have watched young conductors from the school learn and grow on the spot.

“They’re all dressed in their tuxedos and they might conduct one movement of a symphony,” Lasater said. “I think that’s an important thing Robert does to keep these young conductors moving to a higher level of developing their skills.”

Nearly 200 musicians apply for the conducting school every summer, but Spano only works with 10. Spano said six or seven applicants are admitted, and returning students fill the remaining spots.

“It’s highly competitive,” Spano said. “Because of that, the people who come are brilliant. They’re so talented, so smart, so musical, that it’s a joy to work with them.”

Spano’s teaching days date to high school. He taught music lessons to fund his own composition, conducting, organ, flute, French horn, piano and violin lessons.

Eventually, that became a career path. A few years after graduating Oberlin College and Conservatory in 1984, Spano started teaching there. He worked full time for five years and continued part time for nearly a decade while picking up more conducting and performing roles.

The teaching load at Oberlin had mostly disappeared by the time Spano took the Atlanta music director role in 2001. Aspen’s conducting academy helped fill that gap. Spano also created the Atlanta School of Composers while with the ASO.

“Finding that way to try and facilitate someone else’s understanding, I’m endlessly fascinated by that,” Spano said. “I love the process of teaching. It’s a reward that I don’t know anything quite like. When people you’ve helped do well in the world or for themselves, there’s a personal satisfaction.”

At 14, Spano determined conducting could be another career option. He conducted a self composed piece of music and discovered that, instead of specializing in one instrument, as many people had suggested, he could learn more instruments and use the knowledge as a conductor.

Growing up around musicians, Spano seemed destined for the music industry. His parents, grandparents and uncles played instruments.

That influence helped shape the award-winning musician. Spano is one of two classical musicians inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, and has received four honorary doctorates and won four Grammy Awards.

He has traveled the world, teaching, conducting and playing music.

“We’re lucky,” Lasater said. “We’re very, very fortunate. I hope more and more people realize that and keep coming and fill the hall. It’s a splendid experience.”

CHASING PERFECTION IN A NEW WORLD

“Lucky” is a word that keeps coming up in association with Spano. Musicians and staff members say it in reference to the talent, skills, expertise and spirit Spano brings to the symphony. Even musicians outside the organization have taken notice.

“I have friends in other orchestras who say, ‘Robert Spano is your music director. How exciting!’” Shih said. “Everybody wants to sort of join in the excitement. It’s been wonderful.”

The symphony’s second season under Spano’s direction opens Sept. 8-10, featuring music by Schumann and Brahms. Yunchan Lim, the 2022 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition winner, will join in performing Schumann’s “Piano Concerto.”

Spano looks forward to the new season and will continue racking up air miles while fulfilling guest-conducting commitments.

He does miss a certain furry family member though while traveling. Maurice, a 10-year-old black pug, helped Spano explore their new home last fall. They uncovered popular downtown attractions, like the Fort Worth Water Gardens. Maurice has been with Spano’s relatives most of 2023 since the conductor’s travel schedule has picked up steam.

“He’s better than people,” Spano said. “He takes me [on walks]. I don’t take him. He’s in charge.”

When he’s at the loft, it’s not uncommon for Spano to pull a book off the shelf, flip on the television and unwind from a long day of orchestra rehearsals, meetings or travel.

He might watch DVR recordings of “The Big Bang Theory,” “Everybody Loves Raymond,” or “Seinfeld.” During the commercial breaks, he will read a few pages of the selected book and then return to the show.

As Spano settles into Fort Worth, one thing remains certain. He will never let the symphony stop chasing perfection.

“Anyone who does creative work is constantly trying to chase after that vision or dream or the possibility of something that’s mwaa,” Spano says while doing a chef’s kiss. “The orchestra has that in rehearsal. We’re not so good at not judging, criticizing and evaluating ourselves, because we all do that. There’s an aspiration level to what we’re doing that never goes away.”