By Marilyn Bailey

Above photo by Ron Jenkins

Curator John Rohrbach gives us a closer look at photographer Gordon Parks

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art reopened in September with refreshed and rethought interior spaces that tell the story of its collections in a newly engaging way. A visiting exhibit that opened at the same time: “Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940-1950,” delivers a big moment, too.

John Rohrbach, the museum’s senior curator of photographs, says he had long been looking for a show devoted to Parks, the brilliant and pioneering African-American photographer who also was an accomplished writer, musician and filmmaker (he directed Shaft). “This show in particular interested me because it captured the formative decade of Parks’ career when he shifts from being a fledgling portrait photographer at the beginning of the decade — he’s self-taught and had only been photographing for three years — to the end of the decade, when he was invited to become a staff photographer for Life magazine.”

And in 1950, that was the pinnacle. “If you got to be a staff photographer at Life, you were one of the world’s most important and respected photographers. Doors opened up to you. Other photographers would look up to you and try to mimic you. To do that as an African-American photographer in this era was remarkable.”

Rohrbach helps us understand Parks’ rapidly expanding skills through a closer look at five images in the show.

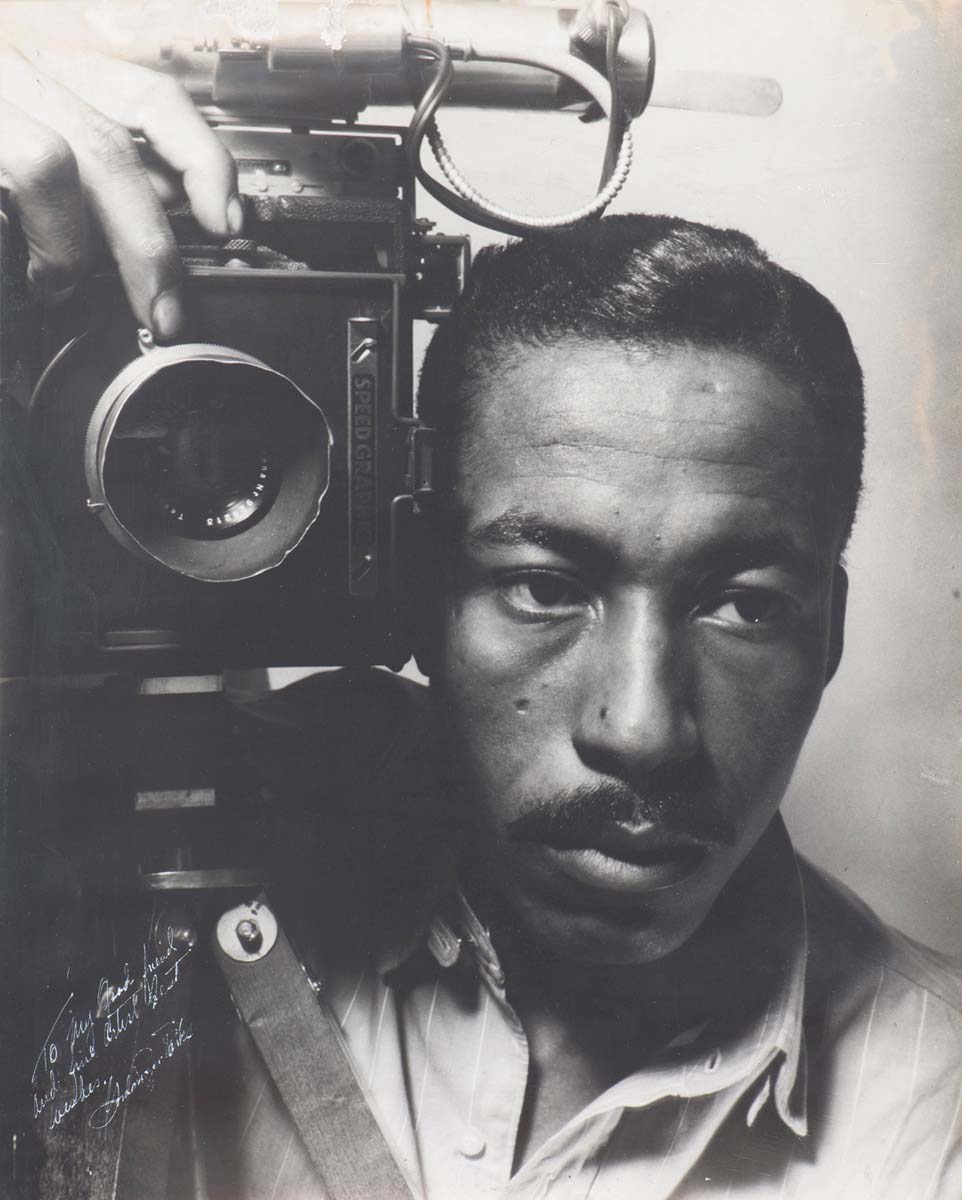

Self-Portrait

1941, gelatin silver print

“Now if that’s not a portrait of somebody who’s self-assured, I don’t what is. He’s not even looking at us. This is a portrait of the camera as much as it is of him. And it speaks to his ambitions, of his sense of self-presence. He feels he’s just as good as all of these people he’s photographing. He’s learning from them, and they think he’s somebody who’s ambitious, who’s got great talent, who’s got a good eye and we’re going to help him out. And that really sends him on his way. It’s really a remarkable portrait.”

Marva Trotter Louis, Chicago, Illinois

1941, gelatin silver print

Parks’ talent is apparent in the earliest images in the exhibition. Living in Minneapolis with a day job working for a railroad, he began photographing African-American social events for local publications. He also approached women’s boutique owners about photographing their clothes for advertisements. In this image, he shows an instinctive flair for fashion imagery. “He made the shadow of Marva Trotter Louis almost as dominant or perhaps even more dominant than the figure herself. He’s interested in going beyond the obvious.” As the wife of boxer Joe Louis, Marva Trotter Louis was well-positioned to help Parks. She lured him to Chicago and introduced him to important people. “He enters a totally different milieu. Charles White is painting a huge mural for the Chicago Public Library, Langston Hughes has stopped in Chicago to start a theater group. [Their portraits are in the show.] He meets Richard Wright, he meets all of these major cultural figures. Imagine being a fledgling photographer and suddenly being part of that group.”

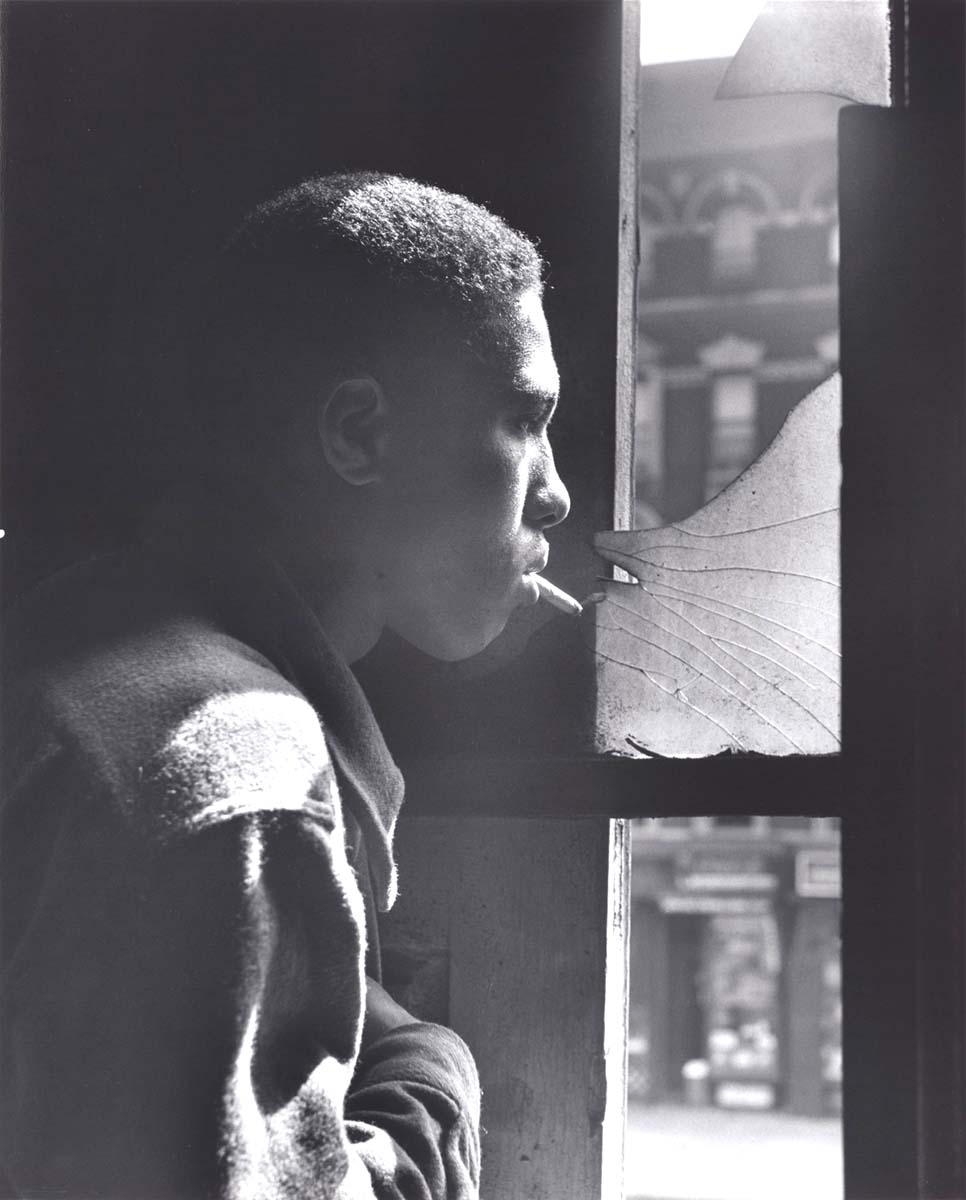

Trapped in abandoned building by a rival gang on street, Red Jackson ponders his next move

1948, gelatin silver print

Parks is living in Harlem, where he decides to photograph a gang and focus an entire series on one person. Red Jackson was a 17-year-old gang leader. Parks captures Jackson standing next to the coffin of a fellow member, but also an image of him reading at home. “He doesn’t hide the violence, but he also shows all the other aspects of Red Jackson’s life,” Rohrbach says. In this portrait, “you try to imagine what he’s looking at in the street, which looks pretty vacant and clean, but you know it’s scarred with violence. And all [Parks] needs is the light coming in the window. Remember the grease plant, where he’s taken all these lamps and put them all around him? Here, he merely takes the light of the window and lets everything else go dark. Red Jackson is looking out of darkness into that light and figuring out how he can live within that broader lit community. It’s just a beautiful portrait.”

Pittsburgh, Pa. The cooper’s plant at the Penola, Inc. grease plant, where large drums and containers are reconditioned

March 1944, gelatin silver print

Standard Oil hires Roy Stryker to help burnish its image, and he puts Parks to work photographing America’s oil and gas industry. Here, he shows us a scene inside a grease plant. “It’s filthy, dirty, really slippery work. What Parks has done to create this portrait is really amazing. Just try to walk into an area that has that much steam and filth and try to keep your camera clean, for one thing. He has taken three banks of lights and synced them all to his camera to light this figure so he’s not all in shadow. Then he gets way down below to look up to this person. Parks is slipping and sliding because there’s so much grease around, but he makes a heroic, graphically clean, exciting image. … It’s the heyday of picture magazines, and he’s training himself to make graphic images that will catch somebody’s eye — make them stop, make them look.”

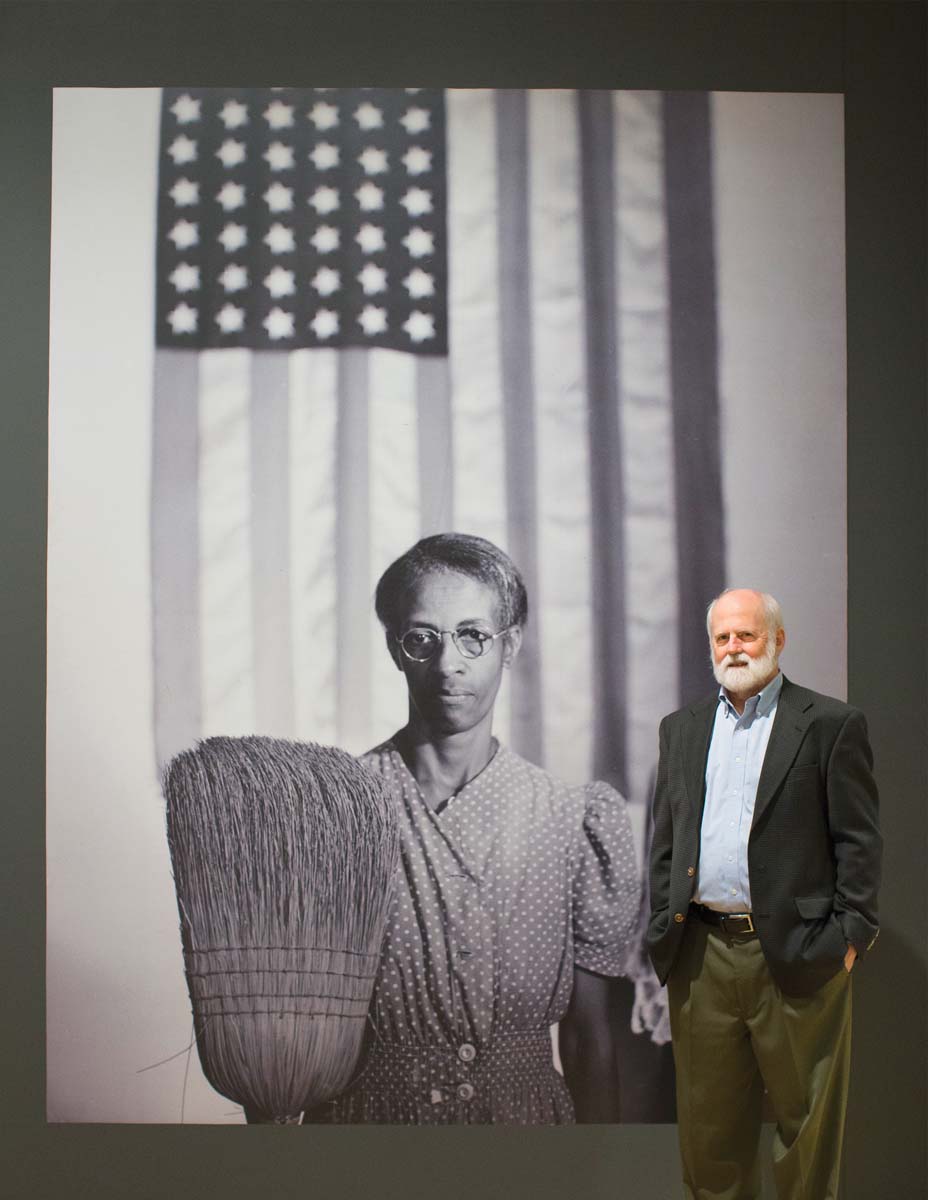

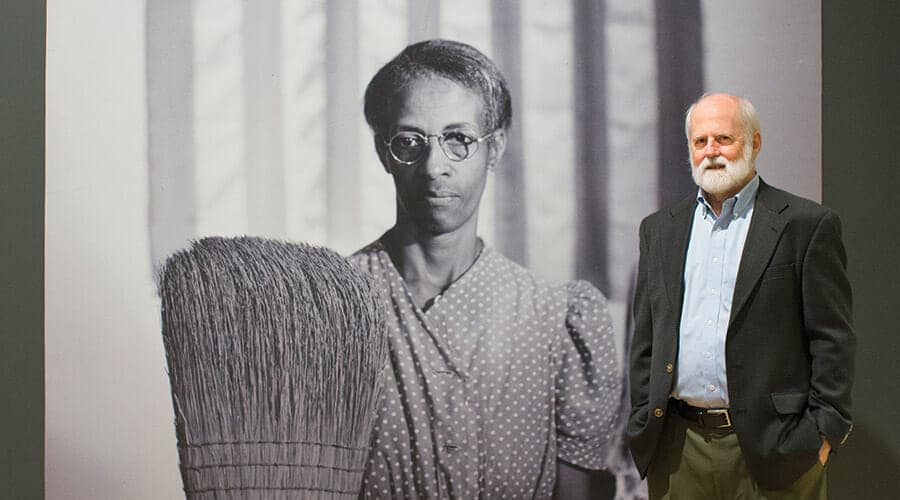

Washington, D.C. Government charwoman

July 1942, gelatin silver print

Parks goes to work for Roy Stryker, who’s in charge of a group of social-documentary photographers at the Farm Security Administration, people like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. Stryker asks Parks “to move beyond single images and tell a story that’s fuller through groups of images,” Rohrbach says. They settle on the office cleaning women, and he wins the cooperation of Ella Watson, who has done this work for 35 years. It was the first Fourth of July during America’s involvement in World War II. “It was time to wave the flag,” and many mass-circulation magazines had put the flag on the July cover, so Parks wasn’t drawing only on his own imagination, Rohrbach says. Still, “he sticks a broom in one hand, a mop in the other, and she becomes a symbol. It’s such a heroic, graphic, easy-to-understand, easy-to-read image that it takes off and becomes his best-known photograph.”

THE DETAILS

Amon Carter Museum of American

Art The Gordon Parks exhibit runs through Dec. 29. 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth, 817-738-1933, cartermuseum.org.