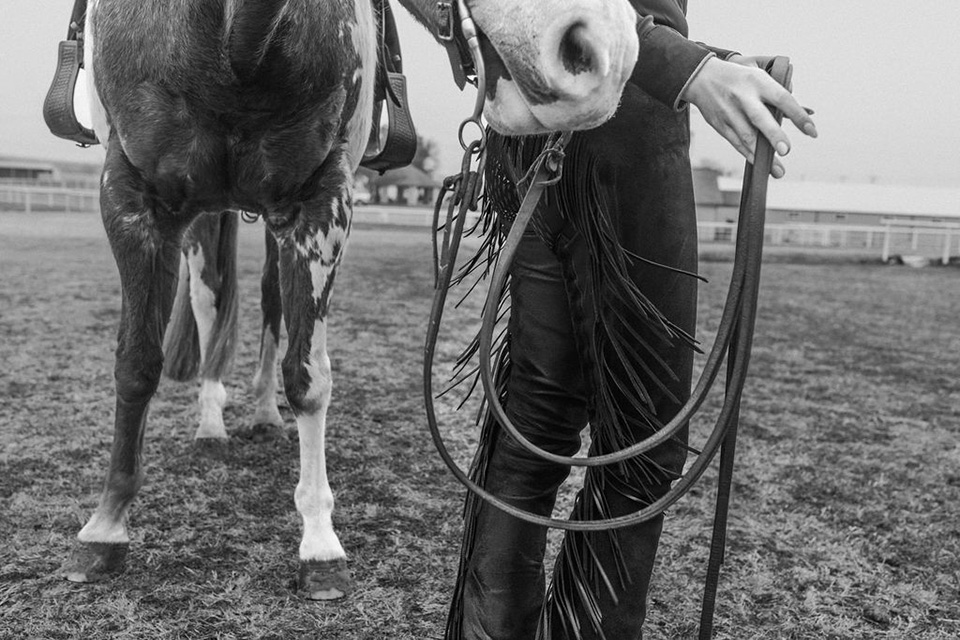

TCU equestrian offers two disciplines: Western and English. Payton Boutelle (left) competes in Horsemanship, a Western event, while Ashleigh Scully rides in both English events, jumping seat fences and equitation on the flat.

TCU equestrian team prepares for Big 12 championship and a shot at glory

By Tori Couch

Photography by Crystal Wise

On a partly cloudy February morning at Bear Creek Farms, Texas Christian University (TCU) equestrian riders guide horses in and out of a riding arena.

Incoming riders warm up for practice as the exiting riders take their horses to wash stalls. Horses are washed down with a hose, brushed and returned to their stalls. Riders hang bridles in a tack room under a horse’s name tag.

By the time the last practice is done and the barn is cleaned up, it’s nearly lunchtime. Riders still have afternoon class, homework or other school-related responsibilities on the docket. And the women will be up early again the next day for a 6 a.m. weight-lifting session followed by practice.

It’s all part of being an equestrian student-athlete.

“It’s hard, but I think we all love it so much that we make it work,” junior Lannie-Jo Lisac says. “It’s easy for me to wake up and go to workout and come to practice and then go to class. So, that’s never been a challenge for me just ’cause I really do love this so much that this is all I want to be doing.”

Horses are considered teammates. Each student-athlete takes care of a horse before and after practice.

Preparing for a Meet

Bear Creek Farms is about 20 miles south of TCU’s campus off Chisholm Trail Parkway in Burleson. Signs surrounding the facility and on the barns tout it as the home of the No. 2-ranked TCU equestrian team.

Expectations are high this year with sights set on a Big 12 Conference title and a return to the National Collegiate Equestrian Association (NCEA) National Championship after a runner-up finish last season. The Horned Frogs posted a 5-3 overall record (3-0 in Big 12 meets) during the fall and opened the spring with a 16-4 win over South Dakota State at the Fort Worth Stock Show & Rodeo. TCU will host three more meets this spring, including the Big 12 Championship in March.

TCU added equestrian as a varsity sport in 2006. The NCAA—college athletics’ largest governing body—considers equestrian an emerging sport, which means teams must follow NCAA rules but the NCEA conducts the national championship and serves as a governing body to advance the sport.

TCU competes in the four-team Big 12 and is one of 23 Division I schools that carries equestrian. The Horned Frogs offer Western and English disciplines and each one has two events—reining and horsemanship under Western and jumping seat fences and equitation on the flat for English.

During practice, cars cover the grass area around the barns as 42 female student-athletes, three coaches, a graduate assistant and an athletic trainer are onsite throughout the morning. Student-athletes usually arrive 30-45 minutes before their event’s hour-long practice to prepare the horses. Most of TCU’s 45 horses are donated.

“They come from all over the country in all kinds of different situations,” says Haley Schoolfield, TCU’s director of equestrian since 2013. “They are all experienced show horses in their particular event, but they are all donated by wonderful people from different scenarios and for different reasons.”

To prepare for meets, student-athletes ride a different horse at each practice. Lisac competes in the reining event and notes that horses and riders can gain confidence through these pairings.

“Sometimes you’re more familiar with the horses and you get along with the horse better than you do others,” she says.

Horses are teammates and are given the love, care and attention needed to perform at the highest level.

In addition to post-practice wash downs, riders take horses for walks, clean their hooves and even provide pre- or post-workout therapy. Horses might be placed on a TheraPlate, which uses vibrations to relax stiff muscles, or they’re wrapped in a Bemer blanket to stimulate circulation.

“What all these professional athletes do, we try to do the same thing to our horses because they are athletes just like us,” says Payton Boutelle, a fifth-year graduate student who competes in horsemanship.

Meet Day

All that preparation is put to the test on meet days. When TCU hosts, student-athletes arrive around 6 a.m. to eat breakfast and groom the horses. The host school supplies 20 horses—five for each event—and riders are randomly assigned a horse before the meet.

Riders from opposing teams compete on the same horse and a point is awarded based on who receives the highest score in the head-to-head competition.

Not every student-athlete will compete since only 20 spots are available. Some riders, like fifth-year graduate student Ashleigh Scully, compete in both events within a discipline.

“It is strictly based on who the coaches believe have the best opportunity to win the point on that day,” Schoolfield says. “It’s as simple as that.”

Warm-up riders take horses around the arena so competitors can note things that might affect the ride. Teammates also offer advice if they’ve ridden that horse at past meets. Each competitor then gets a four-minute warm-up before going straight into her event.

During that time, riders quickly connect with the horse.

“It’s definitely tuning into what your strengths and what your weaknesses are and knowing that about yourself,” senior flat rider Laurel Smith says. “And then also getting on with an open mind and listening to what the horse has to tell you on that given day.”

Meets usually start at 10 a.m. and end around 2 p.m., assuming weather delays are not a factor, and events run simultaneously. At home meets, fences and reining compete first followed by flat and horsemanship.

The equestrian team practices at Bear Creek Farms in Burleson, about 20 miles south of TCU’s campus.

Western: Horsemanship and Reining

In the Western arena, Boutelle and Lisac execute specific, pre-assigned patterns.

Horsemanship patterns entail seven to nine maneuvers including walking, trotting, cantering, speed changes and turns. Riders start with a base score of 70 points and earn between -1.5 to +1.5 points for each maneuver.

“There’s a lot of skill that goes with that,” Boutelle says. “And it’s also based on our body position. So, we want a functional body position and also being very connected to the horse. If it looks like we’re not doing much up there, we’re actually doing our job.”

Reining features spins, circles with changes in size and speed and stops, including the dramatic sliding stop. Scoring is the same as horsemanship.

Riders receive the pattern about a week before meets. Each event pattern has similar elements, but in a different order. Veteran riders like Lisac and Boutelle might recognize patterns from years past, aiding the preparation process.

“We’ve all done multiple patterns and there’s only so many that you could do,” Lisac says. “So, once you figure them out, it’s not too complicated.”

English: Flat and Jumps

A neighboring arena houses the flat competition. Smith and Scully ride horses in a 40-by-20-meter area, demonstrating eight movements that are scored individually on a scale from 1-10. The rider’s effectiveness in guiding the horse and position in the saddle are scored as well.

A perfect score is 100 points, but the low-to-high 80s is considered competitive while 90s is exceptional, Scully says.

During the fences competition, riders complete a jumping course while being evaluated on position, smoothness, flow between jumps and number of strides or steps the horse takes in a line.

Like flat, the maximum point total is 100, but a mistake could prove more costly.

“If a horse stops at a fence in jumping, that’s an automatic 40,” Scully says. “It stops again, it’s zero.”

Learning Curves

Watching an equestrian competition for the first time, it can be hard to understand all the technical aspects. This is true for both spectators and riders from other disciplines.

Smith knew very little about Western events prior to college. Lisac expressed a similar sentiment regarding her knowledge of English. Over the last several years, both girls have learned what constitutes good rides in the other discipline.

A voluntary “switch day” during a practice at the end of the fall semester lets riders experience another discipline. Smith has tried both Western events and noticed they require a very different skillset from the English side.

“I have so much admiration for what those girls get those horses to do,” she says. “I wouldn’t be able to get on and do it myself, even as somebody who’s been riding for 12 to 13 years in a different discipline.”

Lisac will watch horse shows with her roommate, an English rider, and try to score the events.

Each discipline requires a different saddle. Western saddles have a horn and are derived from cattle ranches, designed to support cowboys during long work days while English saddles are made for events like jumping.

“The English saddles are pretty small and lightweight and you can carry it under one arm easily. You can carry it on the airplane,” Schoolfield says. “The western saddle has a lot more leather, a lot more hardware.”

Riders might also face a learning curve within their discipline because their high school and college events are not always a perfect match.

Smith jumped fences prior to TCU, but had little flat experience. Lisac did reined cow horse competitions and those skills translated to reining.

Scully jumped fences before college, but still noticed several differences.

“There are kind of different questions being asked as far as the coursework,” she says. “And you’re on different horses and you’re jumping a little bit lower.”

In high school, most riders use the same horse for each competition. Riders participate in regional horse shows or circuits in hopes of qualifying for national competitions.

Those bigger competitions can attract college coaches like Schoolfield. Schoolfield is a registered judge and will scout potential recruits while officiating horse shows.

Schoolfield, Western coach Melissa Dukes and jumping seat coach Logan Fiorentino evaluate everything from a rider’s skillset to her mental toughness. The mental side is important because equestrian has many uncontrollable aspects, like subjective scoring and horses that might act out of character.

“You can only control what you can control and you’ve got to learn to let the rest go,” Schoolfield says. “And working that mental muscle is huge, and so, that’s a piece of why we recruit athletes that have worked under pressure and been under some bright lights.”

TCU equestrian is aiming for its first conference title this spring.

Sustaining Success

At TCU, the lights only get brighter.

Under Schoolfield’s guidance, TCU has produced more than 50 NCEA All-Americans and 15 Big 12 Riders of the Year. Scully earned Big 12 Rider of the Year honors for fences last year and NCEA Co-Flat Rider of the Year honors following the 2022-23 season.

The Horned Frogs have qualified for the NCEA national championship the last 15 seasons with six semifinal appearances and two runner-up finishes. A Big 12 championship remains elusive, though.

Scully, Boutelle and Smith remember the last time TCU hosted the conference championship in 2022. The girls say there’s a different level of excitement and energy at that meet and emotions might run high since it’s their final collegiate meet at Bear Creek Farms.

Securing TCU’s first conference title and unseating the four-time defending conference champion Oklahoma State would make the two-day meet that much sweeter.

“We have our eyes on the prize, eyes on winning the Big 12 championship,” Smith says. “And I just think it would be really cool to do it in Fort Worth, where we have our community right around us.”

THE DETAILS

Upcoming Home Meets

Friday, March 7: Fresno State

Friday, March 28-Saturday, March 29: Big 12 Championship

Location: Bear Creek Farms, 8728 County Road 1016, Burleson