The Soul Searcher

By June Naylor

Photos courtesy of Gerald Kern

As a volunteer at the community food bank, Gerald Kern found that boxing up groceries allowed him to make a difference. But his camera gave him a chance to make a connection.

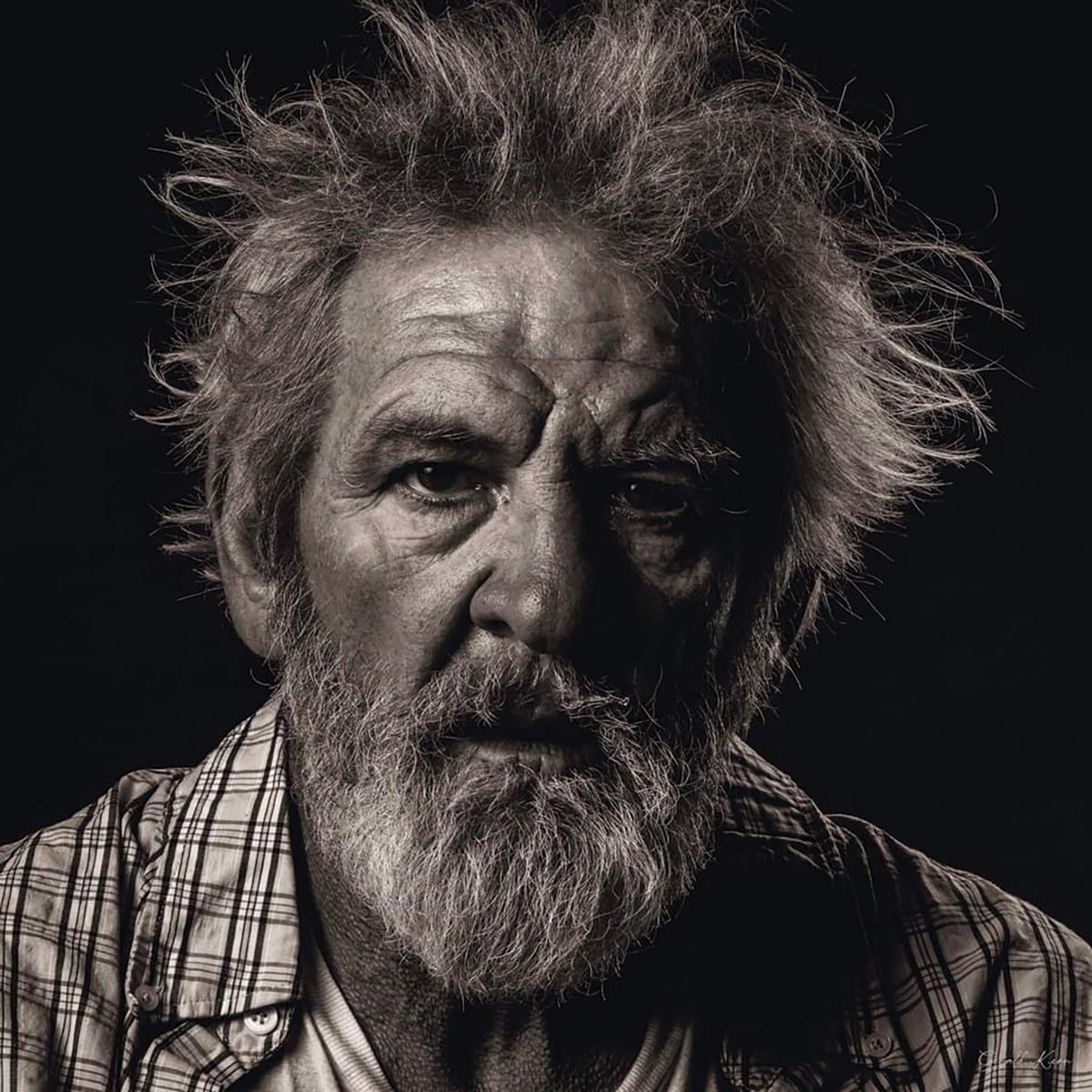

On a spring morning that’s already getting warm at 8:30, Gerald Kern scans a line of people queuing up for boxes of groceries distributed at the Community Food Bank, just northeast of downtown Fort Worth. When he finds an interesting face, he asks if that person might be willing to sit for a photograph in exchange for an extra box of groceries. A woman he approaches on this morning says her name is Pat, and sure, she’ll let him take her picture for additional food. The two friends with her in line — Teresa and Mike — follow along.

Kern leads the three to a makeshift photo studio within the food bank building, where the Trinity Railway Express thunders past on its rails not far away. He asks the trio what kind of music they like; Pat answers quickly that her favorite is classic country. As soon as Kern cues up a Johnny Cash tune on his iPhone, Pat’s face relaxes from tight world weariness to a soft smile. “Yeah, that’s good stuff,” she says, relaxing into the moment.

He snaps photos as he gently asks Pat about her life, and the answers aren’t pretty. She was abused as a girl and ran away from Texas, losing herself to a life in Louisiana that she doesn’t seem eager to talk about. Pat is back in Fort Worth to see a sister who’s in poor health. Teresa volunteers that her abusive upbringing was followed by a life of dancing in bars on New Orleans’ Bourbon Street. Both women admit they suffer from mental illness. Their friend Mike, who wears two walking casts, says little but nods in familiarity with the women’s stories.

Kern spends about 10 to 15 minutes talking to each of the friends while he photographs them, adjusting lights and asking them to change positions as they look at the camera or away. Clearly, the women like being drawn out. Soon, they’re heading back to the group home where they live, the back of their van laden with six heavy boxes of fresh food and nonperishables. They’re a bit more cheerful than when they arrived, which is what Kern always hopes will happen.

“Whether I can use these photos or not, everyone gets 15 minutes of personal dignity while someone listens to their story,” says Kern, who estimates that he has photographed about 1,500 people to date. For every digital image that he thinks he’ll keep, he has shot about 2,000.

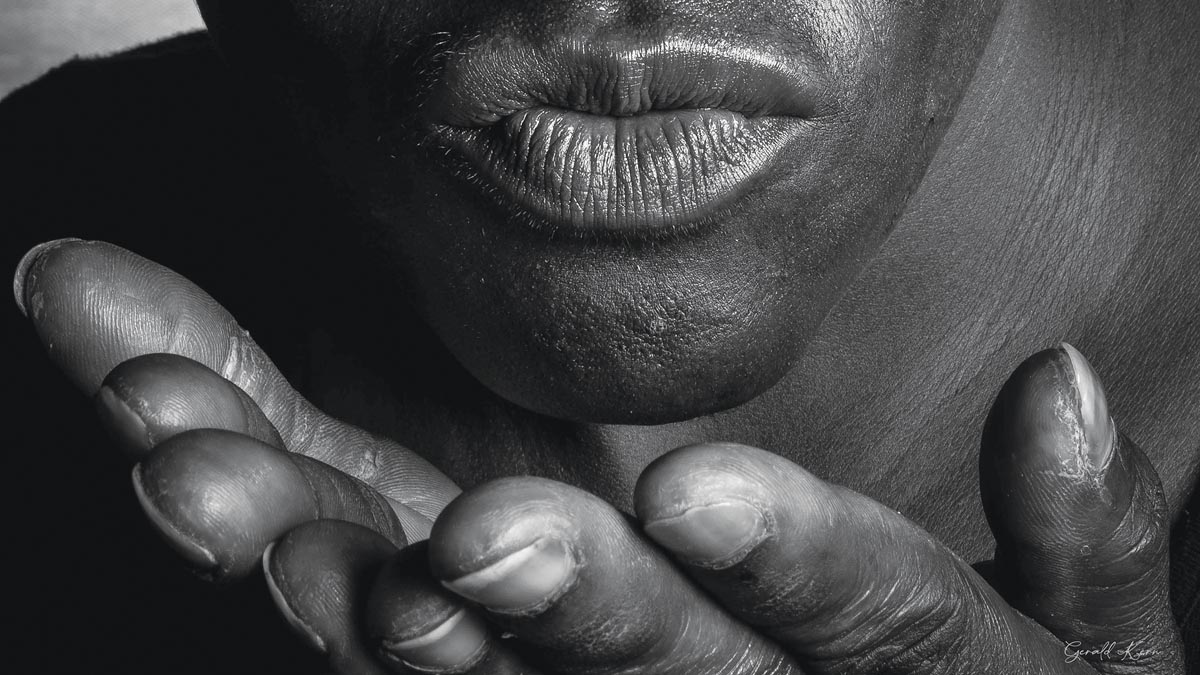

The goal is to amass about 125 photos — ones he hopes will be deemed museum quality — and exhibit them. An early photo called Beatitudes, a close-up of a Black woman’s cupped, upturned hands in front of her mouth and chin, has been selected for inclusion in an exhibit organized by Christians in the Visual Arts.

While the photo project evolved about a year ago, Kern, who lives in Arlington with his wife, a hospital nurse, and their two teenage children, first volunteered at Community Food Bank in the wake of Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Now a member of the agency’s advisory board, he threw himself into helping more at the pandemic’s onset last year. Owner of an events company and a photographer who shoots studio portraits primarily for business types who need resume photos, Kern soon realized that the coronavirus would have a profound effect on everyone — especially those already in need, as well as people whose lives changed the moment they lost their jobs.

“I knew what was happening would be historical and critical, that our population would shift and documenting it would be important,” says Kern, whose project continues today. “And I needed to be here, where I feel at home. When the world was totally insane, this felt like the eye of the storm, because we’re helping people. It’s good for the soul.”

The food bank’s director, Regena Taylor, immediately embraced Kern’s idea: “Gerald is true to our motto of treating all clients with dignity and respect. He introduces them to management, staff and volunteers. He builds their self-esteem; some even leave here in tears of joy.”

Fellow volunteer and former Southlake City Councilman Al Zito echoes Taylor’s sentiments. “Gerald wears a lot of hats, and one of them is therapist. He listens with a lot of empathy. There’s an air pocket you find in doing this volunteer work here, and Gerald finds that place where you can breathe.”

“Gerald wears a lot of hats, and one of them is therapist. He listens with a lot of empathy. There’s an air pocket you find in doing this volunteer work here, and Gerald finds that place where you can breathe.”

Al Zito, fellow volunteer and former Southlake city official

Kern focuses on the beauty within faces that exude heartbreak. His lens captures the ache his subjects know intimately; the look in their eyes can haunt you, whether it’s in the expression of the little girl held by her mom in Mother and Daughter on Riverside or that of the woman with the knife-scarred, sculpted muscles in Shoulders.

Andrew Walker, director of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, is a board member at the Community Food Bank and has worked alongside Kern in a volunteer capacity. He was taken by the photographs and Kern’s process.

“What I found interesting about his project was its start as a general interest in clients at the food bank. Then the camera became a tool to capture their stories.”

Walker noted the parallel between Kern’s approach and the photographs of working-class people in Richard Avedon’s “American West” exhibit, which is included in the Carter’s permanent collection.

“Building on a specific environment the way Richard Avedon did, Kern made the [food bank] setting receptive to the authenticity of what he was doing, and that’s what makes his project so compelling.”

That Kern would find such comfort in this role doesn’t surprise him. Born in Thailand to a Thai mother and U.S. military father, he finished high school in San Antonio and studied business at UTA before serving in the National Guard, where he trained as an intelligence analyst and combat medic with a psychiatry emphasis.

“Working for years in inpatient care and emergency rooms helped my interview skills. The intelligence training sharpened my skills in putting together solutions from abstract points,” he says. “Being able to interview those folks with empathy and compassion helps me get quality stories while capturing a genuine moment in the conversation.”

There’s the Navy veteran who worked as a code breaker and speaks fluent Russian, his promising life shattered when his beloved wife died suddenly. The woman destroyed by the murder of her child by a babysitter. The hundreds of people who just want someone to listen.

Beyond his photography project, Kern rallies influential friends to help in other ways at the food bank. Various projects over the years with NFL luminaries like Drew Pearson and Rayfield Wright, both popular Dallas Cowboys veterans, have steered Kern toward fundraising opportunities. He’s enlisted Wright and his wife, Di Brown, to volunteer at the CFB, where they gather food to supply senior citizens in need near their home in Willow Park, just west of Fort Worth. Further, Kern is helping Wright stage a benefit golf tournament in October, starring other NFL Hall of Famers — an effort Kern hopes will raise big money.

“I don’t live in the world I promote, though. I can’t get caught up in the world of the suites,” Kern says, referring to the more lofty relationships he’s cultivated. “We are not in a Third World country, but right here in the shadows of affluence.” He gestures toward downtown’s high-rises. “We are in a pocket of despair. This place keeps you grounded.”