‘The Sound of Music’ Trapp family continues to gin up nostalgia from its Vermont cross-country ski resort

By Barry Shlachier

Photos courtesy of Trapp Family Lodge

There are other places to cross- country ski, a sport I took up late in life. But there’s nothing quite like Trapp Family Lodge.

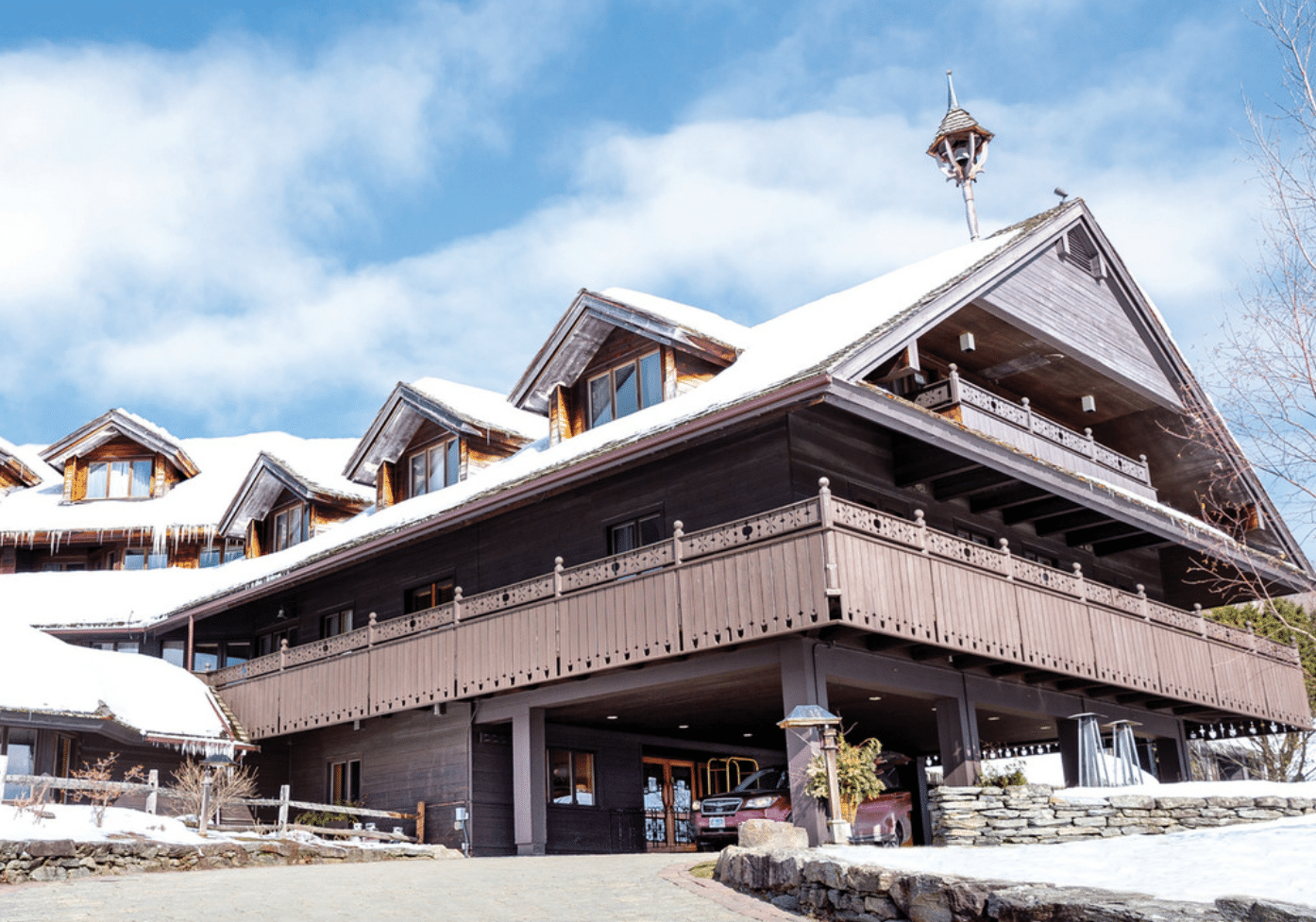

Few places, if any, can boast such amenities: beautifully maintained tree-lined trails; a rustic cabin high up the mountain with warming fire and hearty homemade soups; working farm with shaggy Scottish Highland cattle; maple syrup operation; hand-built chapel up another hill; Tyrolean-flavored main lodge; well-equipped sports center with indoor pool, gym and large outdoor hot tub; and the von Trapp Brewing Bierhall, a world-class brewery and restaurant featuring award-winning lagers and gourmet burger made from the resort’s own beef.

The von Trapps-immortalized in “The Sound of Music” for their resistance to Nazi control of the family’s native Austria – moved to Stowe, Vermont, in 1942 to farm, then offered inn accommodations in 1950. Eighteen years later, the youngest son, Johannes, recruited a ski instructor from Norway and turned the operation into the nation’s first full-service cross-country ski resort. On its 2,600 acres, there are now more than 40 kilometers (25 miles) of groomed trails, aided by a snow-making machine when nature fails to deliver enough. Lessons and equipment rentals are available. (For downhill skiers, Stowe Mountain Resort is nearby with 116 trails and 13 lifts.)

At the main lodge, the “Sound of Music” legacy is hard to miss. The building is festooned with memorabilia and movie posters, both of the Julie Andrews film and two nonmusical films shot earlier in Europe, based on Maria’s 1949 memoir, “The Story of the Trapp Family Singers.” Maria lived in a lodge suite until her death at 82 in 1987 and is buried in a small family plot between the lodge and the outdoor center. Next June, the Vermont Symphony Orchestra and Burlington’s Lyric Theatre Company will perform songs from “The Sound of Music” in a meadow near the lodge.

Johannes’ son Sam, a former Ralph Lauren model and Aspen ski instructor who co-manages operations with his sister and brother-in-law, answers questions following free lectures for guests on the truth vs. Hollywood version of the family history. The true story of the escape from Salzburg, Austria, was gutsy-but less choreographed than that portrayed on film. The baron and baroness led the children on foot to a nearby railway station, which didn’t arouse suspicion among pro-Nazi neighbors given that the family was always going on tour. Austria’s borders were closed the next day.

Capt. Georg von Trapp, a U-boat hero in World War I, had conspicuously refused to fly the Nazi flag after Hitler’s takeover of Austria in 1938, and turned down a Kriegsmarine (Nazi navy) commission. His eldest son passed up a hospital job on learning he would replace a doctor dismissed for being a Jew. And then the family faced uncertain consequences if they refused an invitation to perform on radio to honor Hitler on his birthday. So they decamped for Italy (not Switzerland, as Hollywood had it). The baron presciently had secured

Italian passports since his native border town of Trieste had gone from Austro-Hungarian control to Italian after World War I. They traveled to the United States, then back to Europe when their visas expired, and finally to the U.S. again.

Stories of the real Maria, far stricter and more domineering than the sweet-natured character Andrews portrayed, are still recounted by staff. One employee was admonished by Maria-“That’s tomorrow’s egg salad!” – for tossing out yolks while making decorated Easter eggs.

Some articles over the years said the family sold film rights in 1956 for just $9,000 (equivalent to $101,000 in 2023) to the original German film producer. In reality, there were continuing, though modest royalties from the Julie Andrews film, to underwrite key improvements at the resort, Sam said. “The royalties are less than half of 1%. But it helps.”

Staying at the lodge is not cheap, and its breakfast is a $28 buffet (the Kaffeehaus nearby sells coffee and breakfast pastries), but all the sports activities, including the ski trails, are included in the room price. If you stay one night, you can ski before getting your room and then the following day.

The resort has undergone changes over the years dramatically after the original 27-room lodge burned down just before Christmas 1980, to be replaced by a sprawling, 96-room edifice. Some Austrian decorative touches have become scarcer. But a woman who has vacationed since early childhood at her family’s condominium on the grounds- the von Trapps built several condo buildings on the property — said the lodge’s food has greatly improved. An Old World touch that remains is the complimentary afternoon tea with fresh baked cookies.

Aside from the fire, Johannes’ immediate family weathered a headline-grabbing lawsuit by 20 von Trapp relatives who claimed their shares in the operating company were undervalued by nearly half. They sued for an additional $3 million and managed to remove Johannes from his leadership role for a year. In 1998, Johannes appealed to the Vermont Supreme Court and lost, but his side of the family continues to run the resort.

PERFECT DAY OF SKIING

A perfect day of skiing began by reaching the Slayton Pasture Cabin after a long, herringboned slog uphill. The thick soup, almost a stew, could not have tasted better. Revived, our trip back down was far quicker, but a fast, sharp turn halfway down sent me sprawling, causing a friend to burst into laughter until she, too, landed on her fanny.

Dinner was at the cavernous Trapp Bierhall, which can also be reached on skis. I ordered the superb sausage plate-bratwurst, knackwurst and bauernwurst with sauerkraut- laced mashed potatoes and braised cabbage washed down by a perfect Vienna lager. I would have tried the brewery’s intriguing Maple Rauch lager, made with three malts including a rauch, or smoked type, and a touch of maple syrup. But I was more than full. And satisfied.