By Laura Samuel Meyn

Above photo courtesy of Musée d’Orsay Paris

The Kimbell Art Museum exhibit shines a light on the painter’s twilight years.

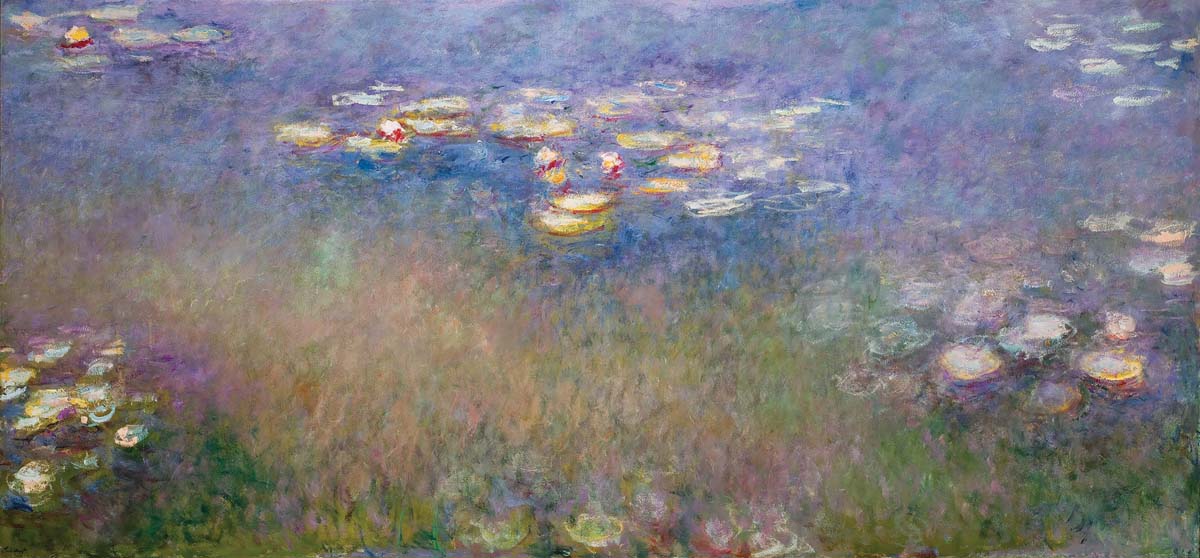

Clusters of flowering water lilies float atop a shimmering expanse of pond, which reflects the sky and also offers glimpses of what grows beneath the surface. It’s a scene that appears in some 250 paintings by Claude Monet, who even had the pond on his grounds in Giverny expanded to gain a broader stretch of water to paint. If you’ve already seen a Monet water lily painting — if not an original, then certainly the reproductions gracing postcards, coffee mugs, even bedspreads — it might be tempting to think that you’ve seen them all. But Kimbell Art Museum deputy director George Shackelford, an expert in 19th-century French art who organized the upcoming “Monet: The Late Years” with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, thinks visitors to the exhibition are in for a surprise.

It was two Monet paintings in the Kimbell’s own collection that inspired “Monet: The Early Years,” shown at both museums in 2016-17. La Pointe de la Hève at Low Tide (1865) and the later Weeping Willow (1918-19) also inspire the new exhibition of more than 50 works, largely from 1914-1926, that opens in Fort Worth this month following a run in San Francisco.

“Late Years” does a deep dive into the beloved water lilies series, showing some 20 examples spanning 20 years, but it also rounds up some of the artist’s lesser known late-in-life works from private and public collections worldwide, most of which were hidden from public view in Monet’s studio until after his death. The exhibition shows how Monet’s style and scale radically shifted during his twilight years, even as several of his favorite subjects remained constant.

A spate of personal losses — his wife’s death in 1911, followed by his son’s death in 1914 — halted the painter’s work temporarily. Three months after his son’s death, Monet returned to painting on a grander scale than before, ordering oversize canvases from Paris. He fully immersed himself in his art, writing to friends of his obsessive, exhausting work sessions. The results showed familiar subjects in a new light. “If a water lily that was about an inch across is painted in 10 brushstrokes, when the water lily gets to be 4 inches across, painted in the same number of brushstrokes, they’re more visible, apparent, gestural,” says Shackelford. “What was quite controlled on a smaller scale seems to be more free when they get bigger. You’ll see in the exhibition a wide range of finish and meticulousness.”

The new direction would be the start to Monet’s greatest achievement: eight large-scale water lily murals that were installed in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris following his death, a final gift to his homeland of France. These “Grandes Décorations,” as he called them, now fill two oval-shaped rooms with nearly

100 linear yards of watery landscape.

Among the paintings brought to Fort Worth for the exhibition is the monumental Water Lilies (c. 1915-1926), on loan from the Saint Louis Art Museum. At 6½ feet tall by 14 feet wide, it’s the show’s largest work, yet it’s only one-third of the Agapanthus triptych. “This is our chance to show you what the really big paintings were like,” says Shackelford. “The painting could very well have been chosen to go onto the walls of l’Orangerie — it really does convey the experience Monet wanted you to have in the end.”

Monet didn’t sell many paintings from this late period; only a handful left his studio before his death. Although there were offers on his water lilies, he refused to sell any of the décorations. When it came to some of his other works, Monet hit a snag that many creatives grapple with — his new style wasn’t immediately appreciated, as they didn’t look like the Monets his art dealers had come to expect. “They were probably flummoxed,” says Shackelford.

An example can be seen in the series of Japanese footbridge compositions. The best known one is from 1899, a peaceful, languid scene of blues and greens, the bridge gracefully arching over the water. However, blurred vision and shifts in color perception due to cataracts caused Monet to undergo surgery in 1923. Around that time, the composition of his works appears far more abstract, with layered, bold brushstrokes in a cacophony of color; only the faint arc of the footbridge makes the familiar scene recognizable.

The artist was reluctant to sell his paintings from this period, indulging in a growing tendency to tinker with them. “He was waiting for the big reveal, which he never saw,” says Shackelford. “He couldn’t let them out of his sight.” Scholars also believe that Monet actively culled his work, destroying what he didn’t want to go public. “A lot of artists do that,” says Shackelford. “It’s reported that he burned them, cut the canvas off wooden stretchers.”

“I think you can almost see the texture and movement of weeping willow tendrils, the whole thing becomes that kind of rhythm of the tangle of the leaves. The final effect is the feeling of movement, plus the intensity and saturation

of color.”

-— George Shackelford

Kimbell Art Museum

deputy director

One late-in-life painting that he did release was the Kimbell’s own Weeping Willow (1918-19), which the artist sold to a Japanese collector, Kojiro Matsukata. “He was the only person to whom Monet sold a painting bigger than 2 meters in each direction,” says Shackelford. “Matsukata’s collections were in Paris, held by the French government until the final treaty between Japan and France [in World War II] and then transferred back to Tokyo. But in the meantime, the French had sold a couple of them, including ours, which was bought by David Rockefeller, who sold it to the Kimbell.”

The weeping willow on Monet’s property was inspiration for a dark, somber series. “Our painting was very personal. It’s almost certainly a statement of mourning for the loss of life his country had undergone with the war. Many villagers in Giverny died; nearby hospitals had wounded from the front sent by a train that crossed his garden,” says Shackelford.

“The tree is a kind of personification of him as the mourner. We know that he was reaching for and finding ways of painting that created great works of art that expressed his new way of seeing.”

THE DETAILS

“Monet: The Late Years” The Kimbell Art Museum’s sequel to 2016’s “Monet: The Early Years” shows more than 50 paintings by the famed French Impressionist from later in life, largely from 1914 to 1926, borrowed from public and private collections around the world. Among the works are more than 20 canvases devoted to water lilies. June 16-Sept. 15. Admission, $14-$18 (free for children under 6; half-price all day Tuesdays and after 5 p.m. Fridays). Renzo Piano Pavilion, 3333 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth, 817-332-8451, kimbellart.org.